For its first production of 2024, Eugene Ballet presents a world premiere ballet from Resident…

The Play’s Her Thing…

Written by Jerril Nilson

Suzanne Haag as Emilia Bassano in rehearsal for Toni Pimble’s Taming of the Shrew

Suzanne Haag as Emilia Bassano in rehearsal for Toni Pimble’s Taming of the Shrew

What brings a certain muse into focus for a creator? The occasional party banter? A bold headline? A societal reckoning with “the battle of the sexes?” Artistic Director Toni Pimble’s vision for her world premiere of Shakespeare’s infamous comedy, Taming of the Shrew, grew out of the universe’s well known capacity for dropping random hints when least expected.

The bold headline—Was Shakespeare a Woman?—leapt out at Pimble in a June 2019 article in The Atlantic written by journalist Elizabeth Winkler. The storied bard’s identity has been questioned for centuries, however, the idea that a woman had penned such literary masterpieces was patently dismissed. Winkler’s research focused on an acknowledged female writer of the time—Emilia Bassano. Winkler writes, “Born in London in 1569 to a family of Venetian immigrants—musicians and instrument-makers who were likely Jewish—she was one of the first women in England to publish a volume of poetry (suitably religious yet startlingly feminist, arguing for women’s ‘Libertie’ and against male oppression.” Pimble had her muse.

Emilia Bassano, 1569-1645 and William Shakespeare, 1564-1616

Emilia Bassano, 1569-1645 and William Shakespeare, 1564-1616

“I like Shakespeare and Katherine is a very strong character,” Pimble said of her choice of Taming of the Shrew. As a ballet, the play has been previously choreographed in 1969 by John Cranko set on Stuttgart Ballet, and in 2017 by Jean-Christophe Maillot set on Bolshoi Ballet. Other than college Cliff Notes, two well-known versions of the play are the 1967 Elizabeth Taylor/Richard Burton film of the same name and the 1999 movie 10 Things I Hate About You. In Pimble’s version, there is a most decidedly female voice playing to the strengths of Eugene Ballet’s female dancers, pushing the boundaries cracked open by the #metoo movement.

At the ballet’s outset, Pimble tasks “Shakespeare” (Bassano) with introducing the play’s characters, as a female hand writes with pen and ink. The classic story arc, marrying for love and/or money, focuses on two weddings: older sister Katherine’s (the “shrew”) to the money-grubbing lothario Petruchio, and younger sister Bianca’s to her true love interest Lucentio. In the two-act program, there is deception, manipulation, and an abundance of fantastical scenery as it all unfolds (don’t miss our next blog post that will detail Pimble’s steampunk vision and collaborations).

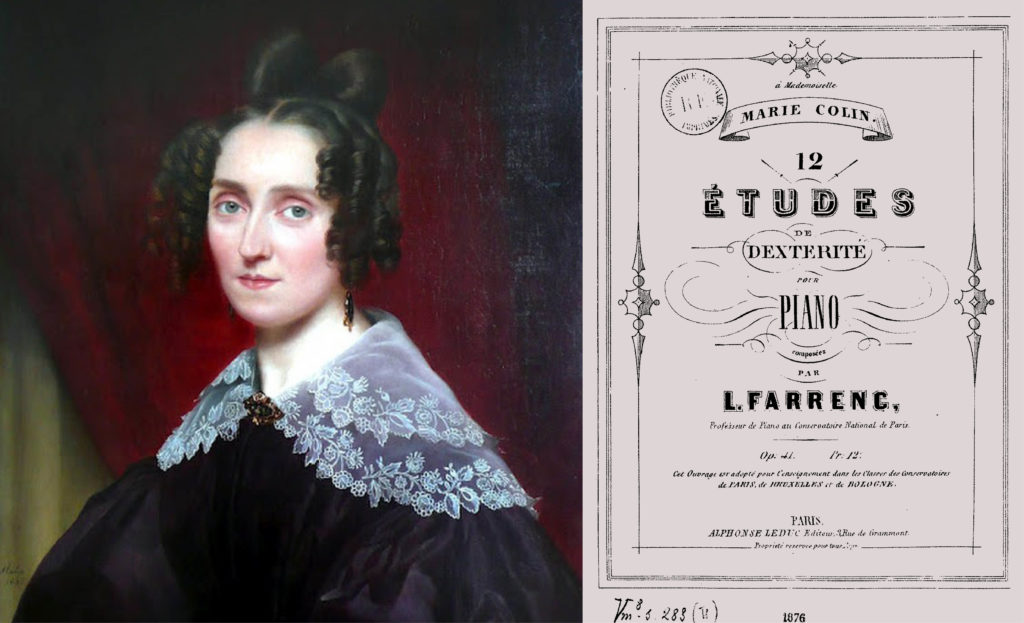

Pimble also takes Taming the Shrew out of its 16th century origins and into the 19th century world of industrial steam powered machinery and its retro futuristic sub genre of science fiction, steampunk. As classical music is most often her choreographic muse, Pimble chanced upon another 19th century discovery: French composer Louise Farrenc. The ballet’s score, including Farrenc’s symphonies and nonets, will be performed live by Orchestra Next. Brian McWhorter, Orchestra Next Co-Founder and Conductor, who had never heard of Farrenc before the project began, explained what makes Farrenc’s music so important:

“First and foremost, Louise Farrenc is a brilliant composer—there’s just no other way to put it! Her scores are master classes in orchestration, melodic writing, and thematic development. Maybe even more importantly for our purposes, her music feels good, which is probably what drew Toni to her music in the first place. Personally, I am so grateful and humbled that I’ve had this chance to study her music so thoroughly, and I can’t wait for our audience to hear it performed live.

Louise Farrenc, 1804-1875

Louise Farrenc, 1804-1875

“But her music is also important right now for the story it tells about women in classical music. During her lifetime (1804–1875) she struggled as you might expect: she had a very difficult time getting her music published and performed, and even when she was hired at the Paris Conservatory (in the Women’s Piano Division) she was paid less than her male colleagues. After her death, her compositions remained unpublished and largely forgotten for more than 100 years. Fortunately, over the last several years, there has been a lot of interest in her work.”

McWhorter and the orchestra have had a longer ramp up to this ballet as it was delayed by the pandemic, and the time was not wasted. “A couple of years ago, we settled on the music for the show which includes selections from all three of Farrenc’s symphonies and her Nonet. The problem is that, as I mentioned, her music is not widely available! So I went to work on making my own edition of Farrenc’s Symphony No. 1 (1842) and I worked directly with her manuscript. This was very challenging work (it took most of the pandemic for me to finish) but it was so rewarding to work with her manuscript that I would gladly do it again,” McWhorter admitted.

“The more I got into Farrenc’s music, the more I became curious about her story. Where did all this incredible music come from?” McWhorter asked. For the answer, check out Orchestra Next’s latest podcast HERE to hear his interview with Farrenc expert Professor Susan Pickett of Whitman College.

With Farrenc, Bassano, and Katherine, Pimble’s muses go beyond the willful female cast in the misogynistic tale. As Winkler noted: “Like Alice’s rabbit hole, Bassano’s case opened up new and richly disorienting perspectives—on the plays, on the ways we think about genius and gender, and on a fascinating life.”

Reserve your seat HERE.