For its first production of 2024, Eugene Ballet presents a world premiere ballet from Resident…

The People of Peer Gynt: Brian McWhorter

By: Anna Herring

When the curtain closes on a Eugene Ballet performance, Orchestra NEXT conductor Brian McWhorter doesn’t want you to remember the score. In fact, he would think it a compliment if you were to say “I didn’t realize what you were playing, but I loved the show!”

That’s because McWhorter thinks that the most effective musical scores are the ones that you forget.

Why?

“For the production, we’re trying to highlight the ballet. Our job in the pit at the orchestra is to play as well as we can, but we’re really servicing a way of telling a story from a physiological standpoint. Telling a story with physical movement; with bodies, with sets and design. There’s a reason the orchestra is in the pit.”

McWhorter, who also serves as the Musical Director for Eugene Ballet and is an Associate Professor of Music at the University of Oregon, is working closely with Eugene Ballet’s Artistic Director Toni Pimble on the production of Peer Gynt in April.

“I like that she (Toni) isn’t dogmatic about what composers to use to tell a story […] I think she is very concerned about music that doesn’t just help her tell the story from a dance perspective, but also music that helps a dancer tell the story.”

The incidental music for Henrik Ibsen’s Peer Gynt was first completed in 1875, as mentioned in the first article of the series. It was known as Edvard Grieg’s Opus 23 (literally, Opus translates to creation). When it was revised in 1885 into the more well known Peer Gynt Suite, the two scores became Greig’s Op. 46 and Op. 55.

However, between the two suites, the music only clocks in at just over 30 minutes, not an ideal length for a full length ballet production. The deficiency of music hasn’t phased Pimble or McWhorter. In fact, if anything, it’s allowed for some creative freedom in crafting the score.

“Even within Grieg’s life, Peer Gynt was malleable. There were movements that he took out, things changed a little with how he saw his work. In Toni’s version, she’s taking the idea of Peer Gynt as a narrative and then adapting it for ballet.”

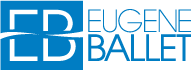

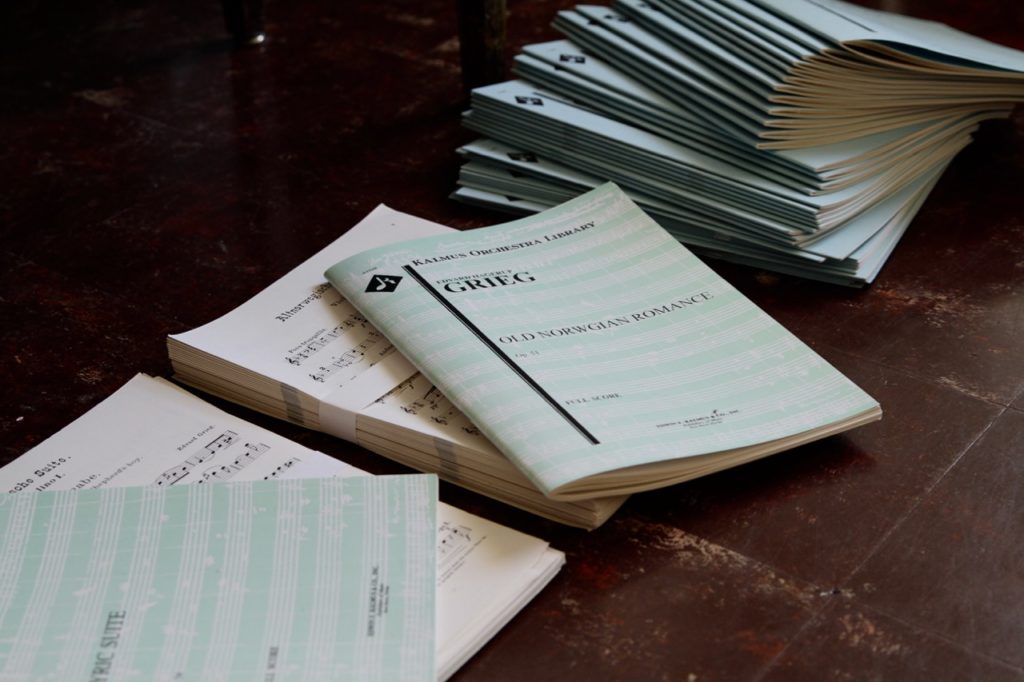

In order to augment the production’s score, 10 different Grieg compositions will be utilized for the production of Peer Gynt.

“When Toni listens to some of this music, she has the narrative in her head, although she’s not fixed with it. She has (conventional) latitude to change the narrative if she likes. She’s listening for music that feels right.”

While the name Edvard Grieg may be unfamiliar, his music is actually more well-known than you might think. Take Hall of the Mountain King and Morning Mood – both songs that we’ve heard played in orchestra performances, commercials, movies trailers and even video games. A version of Hall of the Mountain King can be heard in the movie The Social Network regatta scene.

According to McWhorter, the core of Grieg’s music is about evoking human emotions, common for the genre of romantic music. Grieg’s works are also incredibly simple, and it’s within that simplicity where the music’s familiarity is felt.

“Grieg’s music is unflinchingly folkloric and romantic. And for most of us, it’s as iconic as holiday music. Perhaps that’s why it seems to amplify the fantastical side of Ibsen’s play. It almost sounds like the music is coming straight out of our collective unconscious.”

However, while the music might be simple, putting together a workable score is anything but. McWhorter says the biggest challenge of building a score is constructing the 55 different orchestral parts for all of the instruments, in the right order.

Certainly a daunting task, McWhorter explains that once all of the parts are created, musically speaking, things are easy.

The most stressful part for McWhorter? Being the one conduit between the orchestra and the stage.

“One of the most stressful parts in a new production like this isn’t so much once we get the music going, but in between each tune. Those few seconds of silence are often very nerve-wracking for me. I have to be aware of what’s happening with the set, the lights, the dancers, all of these things are going through my mind.”

If anything, his job is extreme multitasking. But, as McWhorter earlier remarked, the most effective musical scores are the ones that you forget; when he’s doing his best at his job, the orchestra doesn’t notice.

“It’s hard enough to conduct an orchestra and get them to flow. When everything flows, It feels easy. It’s harder to feel that with a company of dancers, but when it does… it’s incredible. It’s a beautiful experience. It’s worth everything.”